Sublime Territories of Launch

Redefining Commercial Space Infrastructure

Roles: Project Management, Design Research, Exhibition Curation

2021 - 2022

Cornell University

2021 Robert J. Eidlitz Travel Fellowship Recipient

Project Type: Academic Fellowship, Speculative Design

Project Status: Exhibition (July 2022)

Project Team: Jordan Alejandro, WELL AP

Collaborating Partners: Cornell AAP, NASA KSC Planning, Kachina Studer

Across America, infrastructure for space activities spans offices, laboratories, factories, testing facilities, and monitoring stations across the continent. This often concealed network of activity culminates with highly visible launch sites around the country, where cutting-edge technology interfaces with pristine coastal landscapes.

This travel fellowship explores the intersection of space technology, industrial infrastructure, and sustainable land use at major U.S. space launch sites. Drawing a 1,200-mile arc along the Gulf Coast and Eastern Florida, the project itinerary spans major U.S space facilities to map the logistics of launch. In particular, the project develops a comparative analysis of two case studies, SpaceX’s Boca Chica testing site and the Kennedy Space Center, documenting the unique environmental and socioeconomic cultures of these sites. The research will be used to project future scenarios of viable spaceport development.

Skills

Academic Research

Master Planning

Architecture

Technology

Rhino 3D

ArcGIS

Adobe Creative Suite

Background

Spaceship Earth

In the seminal book Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1969), the architect Buckminster Fuller lays out the case for conceiving the Earth as a giant spherical spaceship, revolving around the Sun. “We are all astronauts”, he writes, on a planet with finite resources. As space travel became commonplace during the Space Race and the early Cold War, public perceptions also changed about Earth. Objects, people, and places were no longer limited to national or international borders, but considered together on a planetary scale. With the iconic “Earthrise” image, taken aboard Apollo 8 in 1968, the Space Race ignited a broad-based environmental movement, where the public began to consider the wasteful impact of human habitation and seeking new ways to conserve nature. The question today is, just as humans aim to become a multi-planetary species and continue exploring the Solar System, how can we achieve our ambitions while protecting our own Spaceship Earth?

Earthrise, 1968.

Buckminster Fuller, Dymaxion Map, 1943.

NASA: Infrastructure and Monument

NASA’s golden age of spaceflight began in earnest sixty years ago, when President Kennedy made his famous “moonshot” speech and declared his ambition to land an American on the Moon within a decade. Spanning the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs, the United States spent $28 billion to land a man on the Moon, or $284 billion in current day dollars, from 1960 to 1973. To achieve this monumental effort, NASA also established a national network of research centers, testing facilities, and laboratories. By the 1960’s, NASA grew to encompass over 12 national installations, connected together by a brand new interstate highway system and commercial jet airports. This network birthed one of the first systems of logistics in the country - the development, sourcing, testing, assembly, and launch of manned space rockets, spanning some 20,000 private businesses and universities.

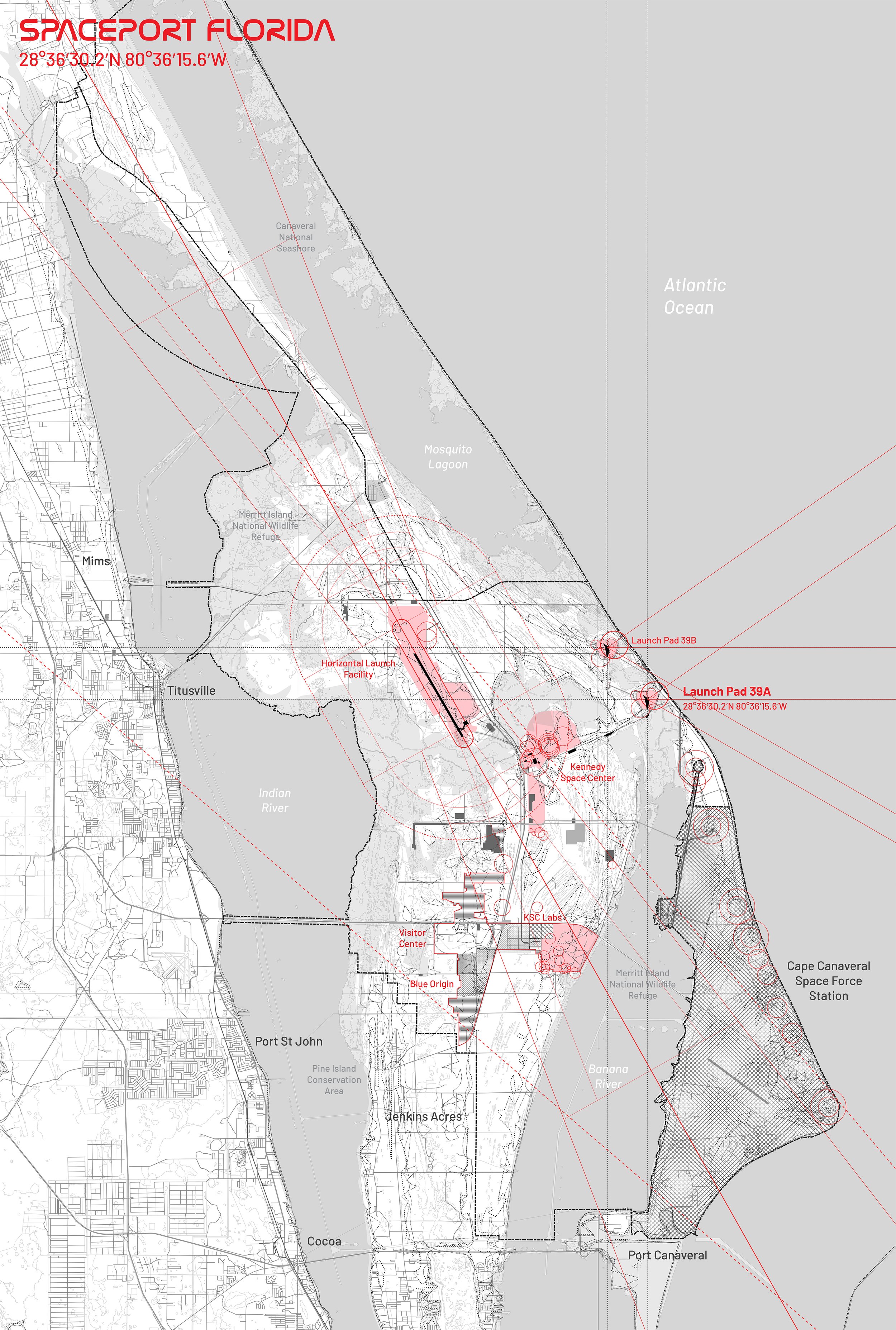

The most ambitious of all NASA installations was the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) at Cape Canaveral, FL. To send the 360-foot Saturn V rocket to the Moon, NASA selected the remote Merritt Island, FL, just north of the existing Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAF), as the future launch site and program headquarters. Encompassing over 144,000 acres, the area was transformed from low-lying marshes and wetlands into a vast 700-building coastal campus. Most notably, KSC includes the 525-foot tall Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB), the iconic Launch Control Center, the NASA Railroad — for last-mile transport of rocket components via ocean barges — and several launchpads (LC-39A, LC-39B) spanning 0.5 square kilometers each. Following the end of the Apollo era and the beginning of the Space Shuttle program in the 1970’s, NASA also constructed a 15,000-foot runway for shuttle landings at the KSC.

Construction of the VAB, 1960’s (Credit: NASA)

KSC in the Present Day (Credit: NASA)

Radical Modernism

Specifically in architecture, NASA’s intensive development during the 1960’s inspired and accelerated new trends in modernism, towards structural efficiency and radical monumentality. In a postwar era marked by Miesian corporate skyscrapers and prefab Case Study Houses, innovators like Konrad Wachsmann merged industrial architecture with the systems engineering ideology of the times. His iconic space frame aircraft hangars in the 1950’s influenced the design of aerospace installations for generations and foreshadowed the rise of mega-scale facilities at NASA. For Buckminster Fuller, his environmental awareness and engineering training inspired his life’s work with geodesic domes, his optimized space frame structures with minimal materials and maximum efficiency. His partnership with NASA triumphed at the 1967 World Exposition at Montreal, where his 200-foot tall Biosphere exhibited the Apollo Command Module and other advanced technologies from the Space Race.

US Pavilion, Buckminster Fuller and Shoji Sadao, Montreal World Expo ‘67.

USAF Aircraft Hangar, Konrad Wachsmann, 1951. (Credit: Atlas of Places)

Space, Today & Tomorrow

With the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011, NASA overall, and particularly the KSC, began a new era of privatization and consolidation. To reduce the federal burden of maintaining the sprawling facility, KSC has embarked on a 20-year masterplan to transition the campus into a multi-use commercial spaceport. Already, the project has found early success. In 2014, SpaceX signed a long-term, 20-year lease for launchpad LC-39A. More recently, Blue Origin, the private space company founded by Jeff Bezos, completed a rocket factory in the KSC Industrial Area in 2020. The KSC’s ongoing planning efforts also devotes significant attention to environmental conservation, biodiversity and climate change. Approximately 95% of the land at KSC is federally protected wildlife areas, including the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge (MINWR) and Canaveral National Seashore (CNS). With the anticipated challenges of sea level rise on the horizon, the low-lying marshlands of the KSC are expected to encounter prolonged flooding and inundation, threatening both the local biodiversity as well as KSC operations.

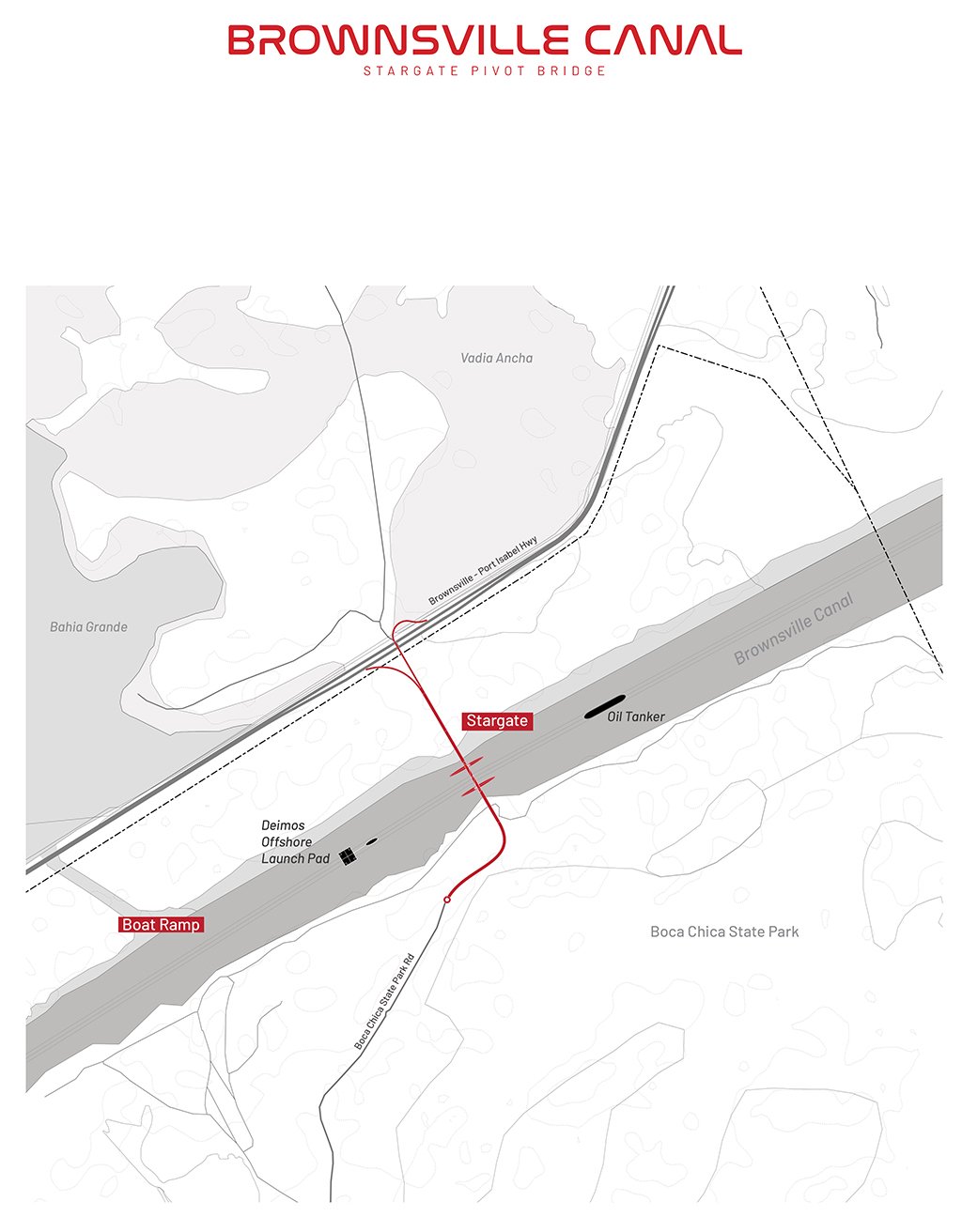

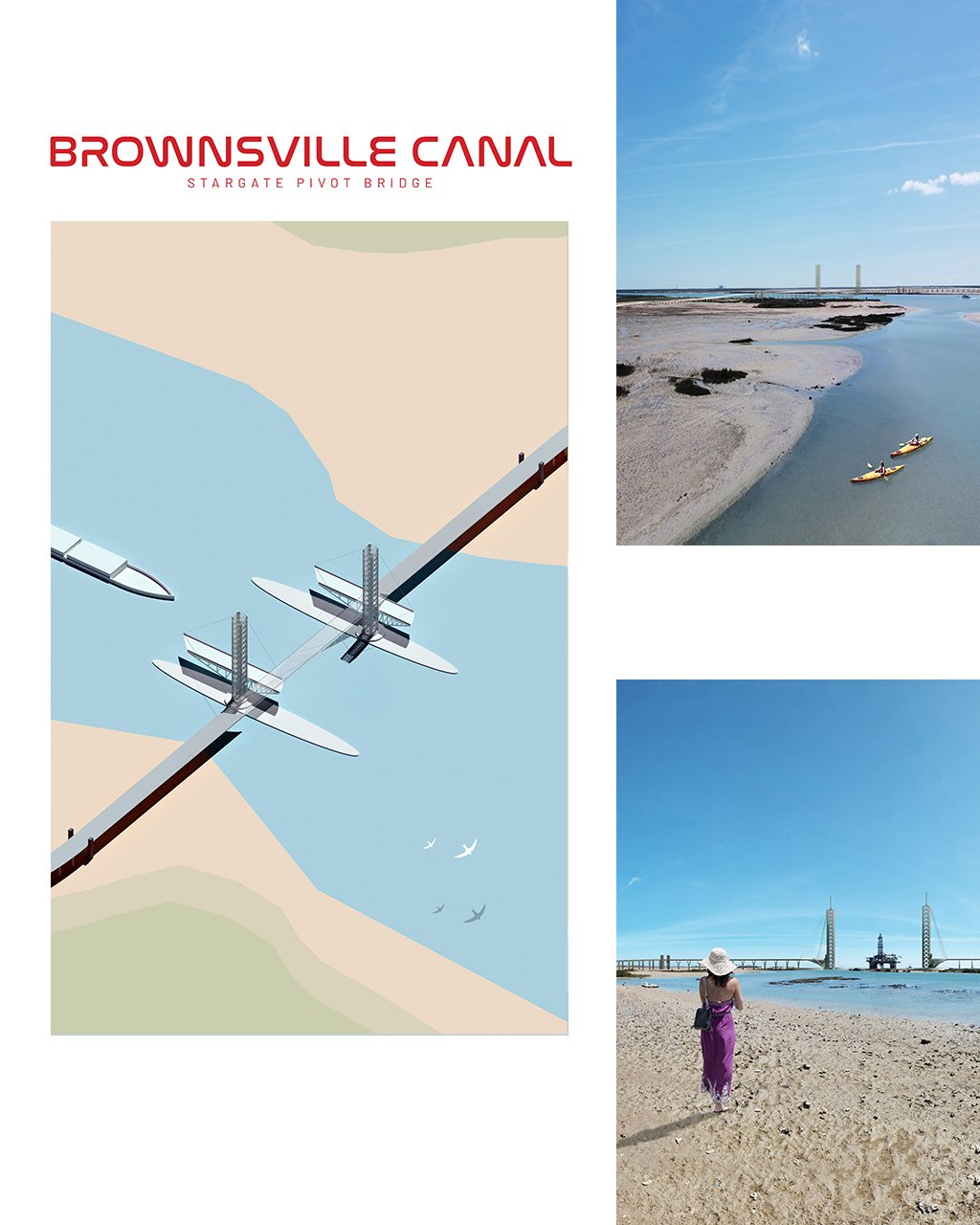

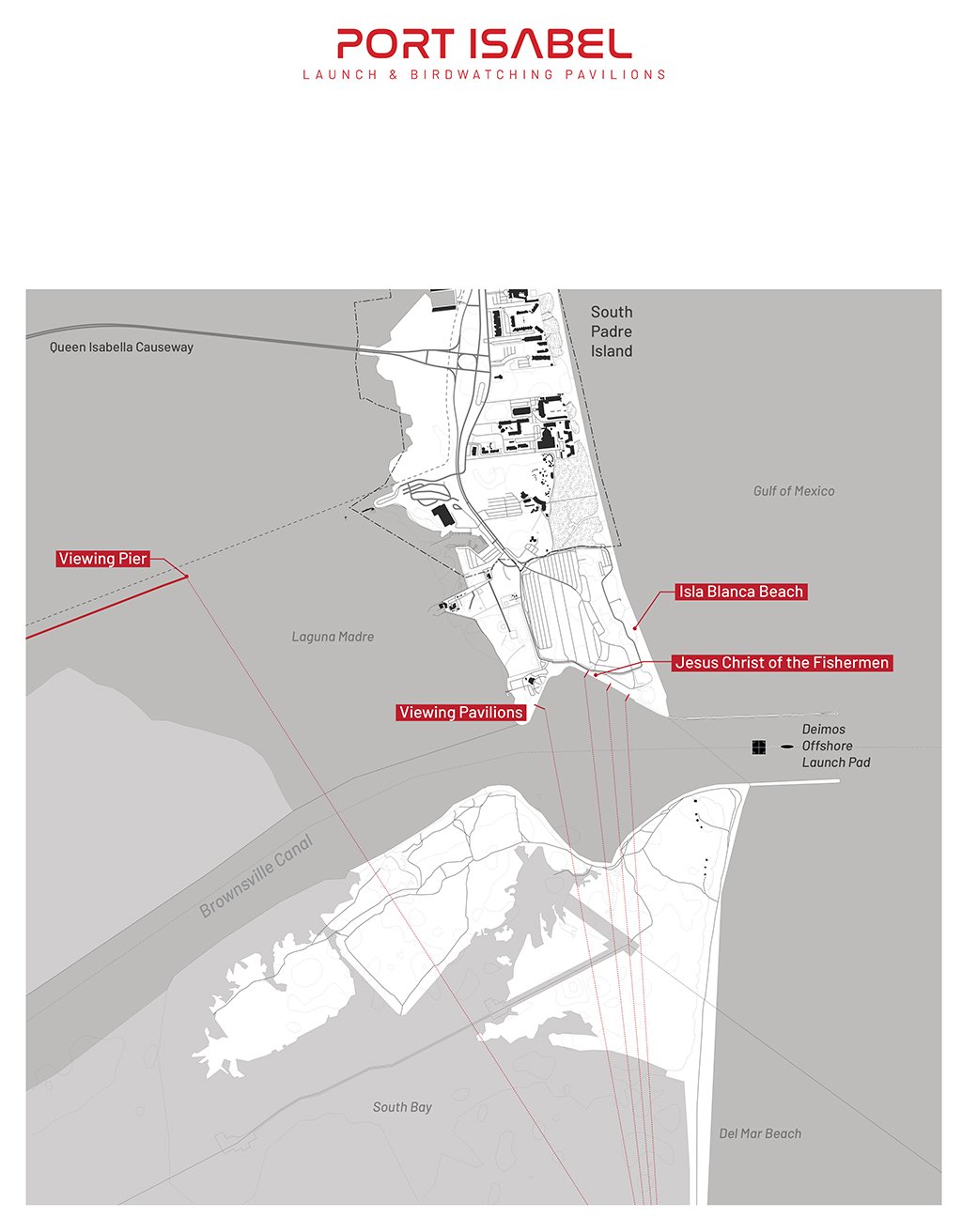

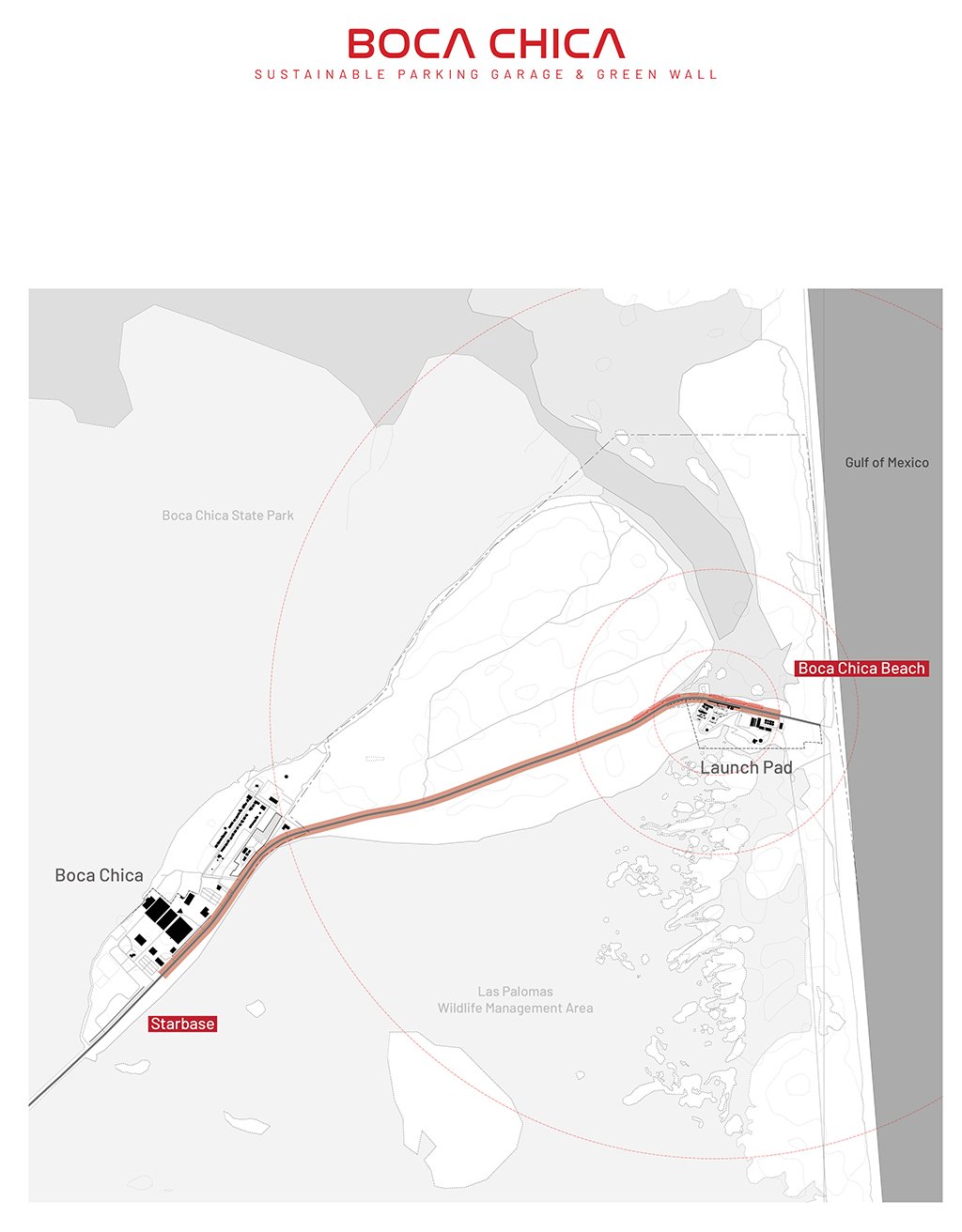

Parallel to KSC’s efforts to build a world-class spaceport, SpaceX has also begun developing their own in-house commercial spaceport, nicknamed “Starbase”, in Boca Chica, TX. The private space company has grand ambitions beyond creating reusable rockets and ferrying astronauts and tourists to the ISS. With Starship, the company’s newest super heavy-lift launch vehicle, SpaceX plans to send humans to Mars, as well as to create commercial point-to-point travel between major cities. Key to all these efforts is the company’s Boca Chica launch and testing site. Since 2014, SpaceX has been slowly leasing and purchasing land in the small village near the U.S.-Mexican border and the Gulf coast. In early 2021, SpaceX unveiled preliminary plans to expand its facilities into a 56-acre site.

Stacking Starship and Starship Heavy, 2021. (Credit: SpaceX)

SpaceX Starship Testing Facility, Boca Chica, TX, 2020. (Credit: SpaceX)

Towards a New Space Infrastructure

Considering contemporary trends towards a warming planet and dwindling ecosystems, our project posits the need for a new type of space infrastructure, predicated on climate adaptation and local resiliency. From today’s perspective, NASA’s top-down, systems engineering approach to space exploration did result in extraordinary human achievements, such as landing a man on the Moon and building the International Space Station. However, it also left behind a large environmental footprint on Earth, permanently transforming landscapes and ecologies with industrial debris and derelict monuments. Our new era of privatization and sustainability demands a nuanced, tactical strategy for space travel, one that exists more harmoniously with nature and uses resources more efficiently. Beyond reusable rockets, site-based approaches may include repurposing existing facilities, identifying zones of integration between natural and industrial areas, and responsible eco-tourism. These hybrid scenarios, and other ones to-be-discovered, will more fully manifest the ethos of Spaceship Earth.

Our research applies a critical lens to the practice of space travel, examining how space exploration was done in the past, in the case of NASA, to speculate how we may effectively build and plan in the future, in the case of SpaceX. To achieve this objective, our trip will take us along the Gulf Coast, an important hub of space activity in the United States. Our territories of investigation include:

SpaceX Starbase, Boca Chica, TX

Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX

Michoud Assembly Facility, New Orleans, LA

Stennis Space Center, Stennis, MS

Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, FL

Boca Chica, Looking Towards Starship Launch Site, 2022. (Credit: Author)

Cape Canaveral, Looking towards VAB, 2022. (Credit: Author)